Beyond the Gates: Odilon Redon, Transformation, and the Art of Inner Illumination

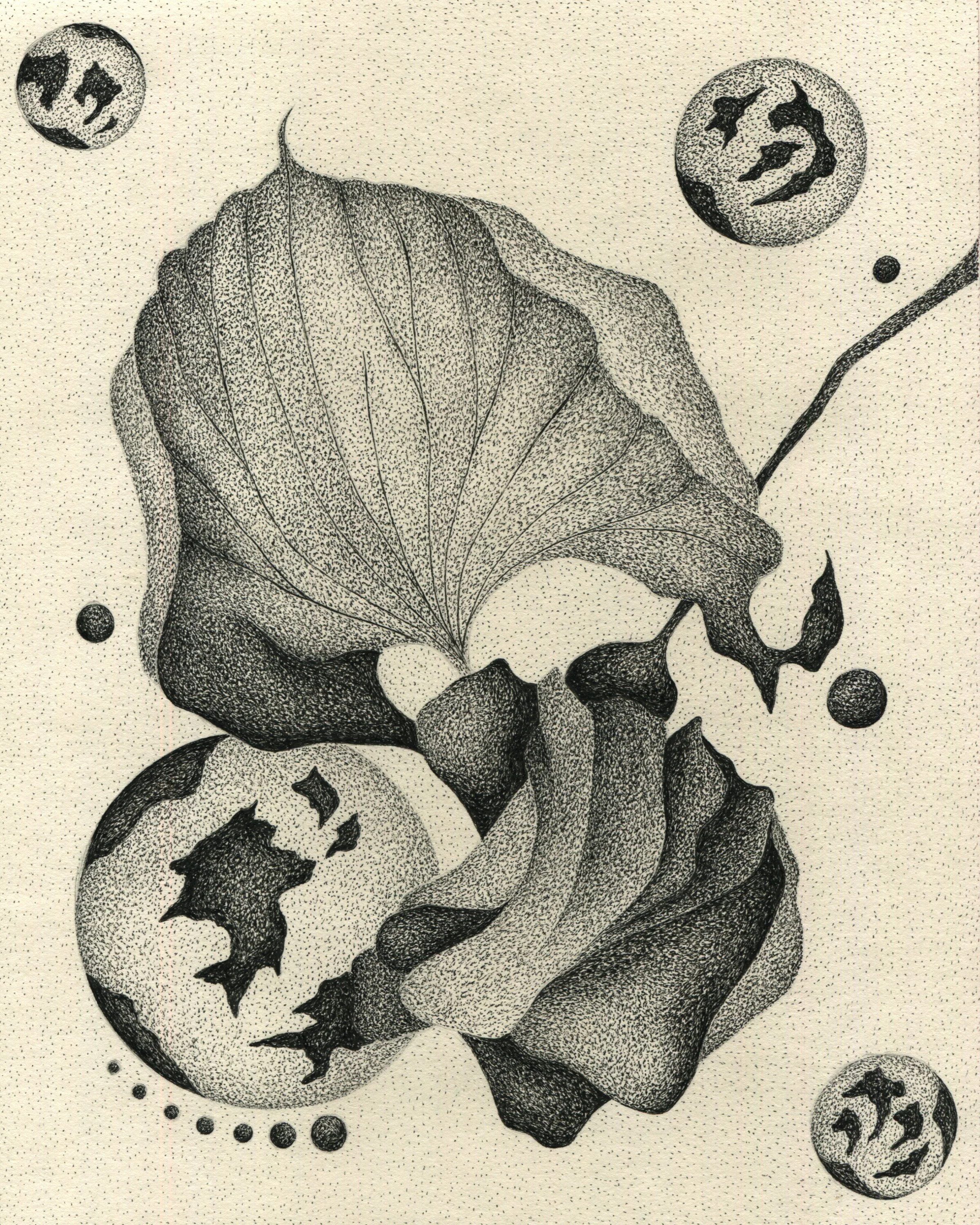

Pen and ink contemporary fine art by Doug Ashby

There are moments in life when, for me at least, the past and future selves seem to collapse into the present. These moments often occur when I am creating, or immersed in something that moves me toward creation. In late April, I experienced such a moment just outside the French National Assembly in Paris. A soft breeze brushed through the air. The sun, warming but gentle, cast a golden hue as I became transfixed by the cascade of tiny spring flowers stretching over the gate. They spilled from trees inside the Assembly grounds, reaching into the pedestrian world as if caught in a threshold. Upon closer look they teemed with life. Bees were diving into blossoms rich with pollen, each bloom in fresh, full expression.

This moment was heightened by a visit I had just made to the Musée d’Orsay. There, unexpectedly, I encountered paintings by Odilon Redon I had never seen before, works that felt radically different from the Redon I thought I knew. These pieces, part of a commission for the Château de Domecy, reflected a profound shift in both style and spirit. Gone were the brooding, monochromatic noirs. In their place were ethereal panels bursting with light and floral abstraction, paintings that seemed to hover between earth and heaven. As I later learned, this dramatic transformation in Redon’s work paralleled a spiritual journey, a movement toward inner clarity that Carl Jung would cite as a visual example of the individuation process. More on that shortly.

Redon was an artist who used his work as a vehicle for personal evolution. He once wrote, “It is precisely from regret left by the imperfect work that the next one is born.” That single line captures the artist’s embrace of uncertainty, imperfection, and change. Each painting became a stage in becoming, not a final product, but a passage forward. A teacher and mentor of mine once warned me of falling too deeply in love with any one piece, because that is often the moment we stop evolving. As I stood before Redon’s work, so different from what I had known, I was struck by how completely he had moved from psychological symbolism to something more spiritual and luminous. His paintings seemed to reflect a convergence of self and nature…a testament to the journey of being here, now, and yet always becoming.

Redon’s early career, what is often referred to as his noir period, was steeped in psychological tension. His charcoal drawings and lithographs depict cyclopean monsters, disembodied heads, and eerie dreamscapes. These works confront the darker dimensions of the psyche, those inner shadows we all carry. To suddenly encounter floral pastels, so unlike those early works, made me pause. What had changed within Redon? What inner transformation had occurred? Was it his engagement with Eastern and Western philosophies? His late marriage and the birth of his son? Or perhaps the inevitable wisdom that comes with age and introspection? Whatever the cause, the shift was unmistakable: his work had traveled from darkness into light.

Carl Jung identified this trajectory as a manifestation of individuation, the process by which we integrate the unconscious, including our shadow selves, into a more unified whole. The shadow, Jung said, includes our fears, impulses, and hidden potentials. It is not to be rejected but embraced. Redon’s early works can be seen as encounters with this shadow, symbolic explorations of fragmented selfhood. Through years of artistic and spiritual practice, his later work reveals a greater integration: a Self coming into focus, light emerging not by denying the dark, but by absorbing it into wholeness. Jung believed art was a powerful instrument in this process, allowing unconscious content to surface through symbols, dreams, and images. Redon’s body of work, from noirs to fond clair, is a luminous archive of that evolution.

One quote from Redon resonates deeply with this idea: “My originality consists of putting the logic of the visible at the service of the invisible.” For me, that is the essence of art’s power, to hold, communicate, and translate what cannot be said in words. As an art educator, I often tell my students that art is a conversation between the artist and the viewer. It speaks in a language of color, form, and feeling that bypasses logic and moves directly into spirit. Redon’s words helped me understand more fully why I create, not to explain, but to reveal. The flower I saw outside the Assembly gates reminded me of this: a symbol that existed between boundaries, offering an emotional and spiritual glimpse into something beyond.

People often ask me to defend abstraction in art. I understand the discomfort, abstract work lacks the narrative anchors we’re used to. But Redon’s evolution toward abstraction, away from specific imagery and toward dreamlike interpretation, shows how abstraction can invite deeper presence. In my own work, I lean toward abstraction rooted in familiar forms. Organic shapes, celestial motifs, landscapes that feel almost known. Whether fully abstract or semi-representational, art can hold space for the ineffable, giving form to feeling and calling the viewer into dialogue. Like Redon, I believe that abstraction is not about evasion, it is an offering.

As an artist, I strive to bring my process not only into the work itself but into my writing and reflection. I want to create a space where viewers participate in the journey, not just observe it. The creative path is nonlinear, uncertain, and often disorienting. But in Redon’s life, I see a model for embracing that tension, of carrying forward the shadow while moving toward illumination. He never completely left behind his earlier themes, but he allowed them to transform. That is the work: not discarding the past but metabolizing it into growth.

What stirred me most deeply in the Musée d’Orsay that day was not just the beauty of Redon’s work, but the challenge it offered. To stand with it was to accept an invitation, not only into Redon’s transformation but into my own. I didn’t leave the gallery with clarity, but I left changed. Art rarely gives us resolution, but it can mark the turning of a path. It can nudge us toward our next direction, if we are quiet enough to listen.

Later that morning, standing again before the flower outside the National Assembly, I paused at the threshold. I let the moment speak. The flower, singular among thousands, floated in time, and I allowed myself to float with it. The spirit of Redon’s transformation echoed within me. His paintings had opened a gate. Art does that, it lets us peer just beyond the edges of certainty, into the uncertain and what might yet become. That morning, with Redon’s vision still blooming in my mind, I knew something had shifted. I had seen where I needed to go, not perfectly, but clearly enough to begin again.

If the above artwork speaks to you, I invite you to reach out. This original 8” x 10” piece is available for $440. Larger commissioned works based on this theme are also available. Please use the contact page on my site to inquire.

If you enjoyed this reflection, I’d love to hear your thoughts—please leave a comment below. I promise I’ll respond.

—Doug