The Vitality Of Food

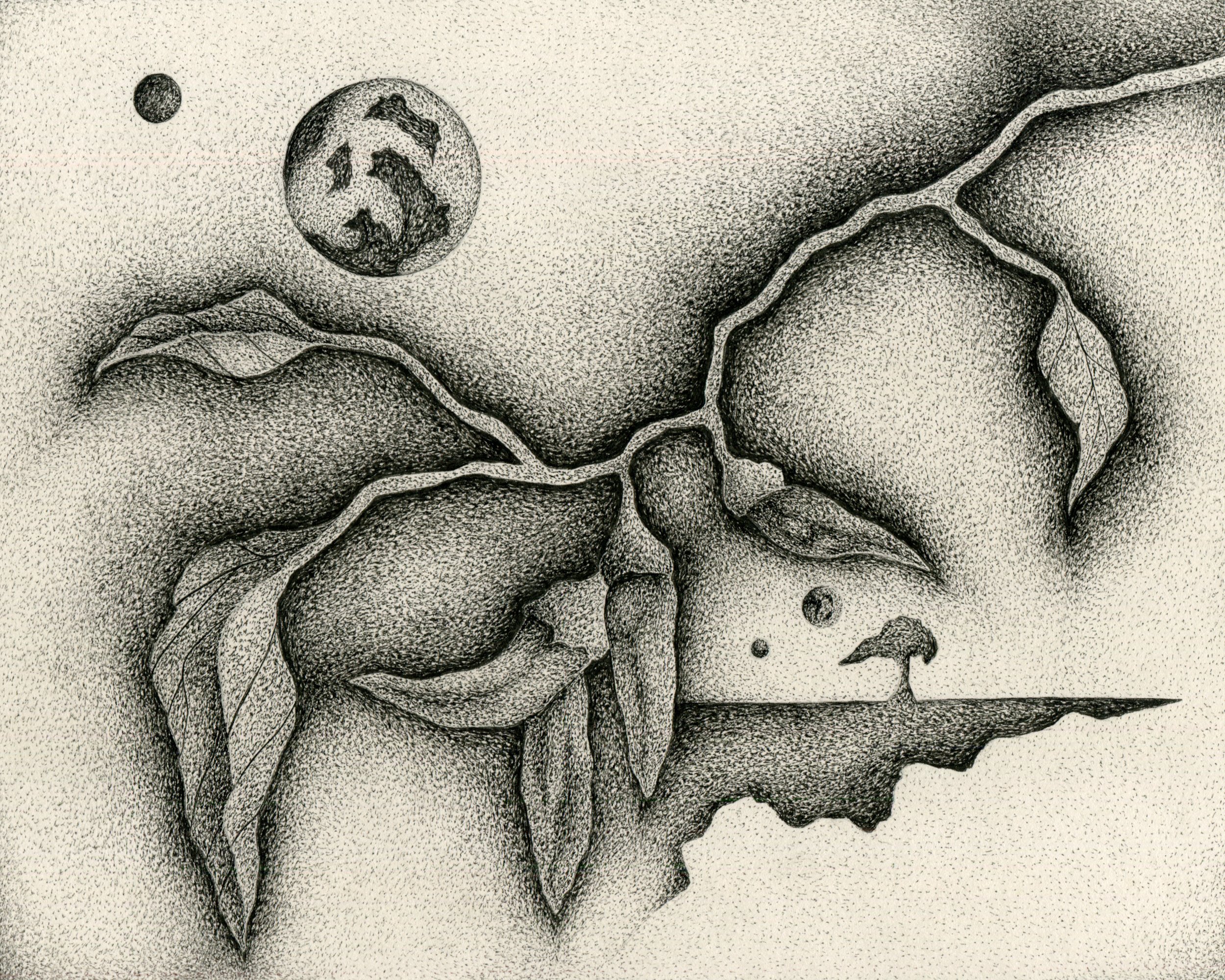

Pen and ink contemporary fine art by Doug Ashby.

Food is an undeniable force in each of our lives. For many years in my early adulthood, I pursued a career in the food industry. The same creative energy that drives my desire to make art often finds its way into my cooking. I can spend hours daydreaming about what I’ll cook for dinner on any given day. This artwork is one of many that bridges both realms. It was inevitable that, as an artist, I would occasionally turn my attention to food. Interestingly, the works I create focus less on the specific dishes I dream of and more on the broader impact food has on our lives—from personal health to the environment, and how our food systems affect these areas. Through my art, I strive to provoke curiosity and deeper thinking about what it is we eat.

This particular artwork centers on the humble jalapeño. I’ve always been a lover of spicy food, and when I explore the cultural aspects of food, spice is a recurring theme. The jalapeño often offers just the right amount of heat. On the Scoville scale, it ranks fairly low, but if I want more intensity, I might turn to a habanero. Though I’ve been known to indulge in hotter peppers, I tend to avoid anything too intense, especially as I get older. In this artwork, I wanted the jalapeños to appear suspended in air—weightless, yet intense. My hope was that they would convey a sense of delicacy, a direct metaphor for the precarious balance of our global food systems. A system that could easily fall out of balance if the wrong pressures are applied. We witnessed a glimpse of this during the pandemic, and the sharp rise in global wheat prices following the war in Ukraine serves as another reminder. Perhaps it’s time we consider more diverse food pathways beyond the dominant industrial model.

That path, however, will not be straightforward—and it shouldn’t be. Change is never easy. To build a more resilient food system, we’ll need to be experimental, and perhaps learn to desire less of what has a large global footprint. Resilience might eventually emerge from what we can produce locally. I’m fortunate to live in a region where the soil is fertile and water is plentiful, but even here in New England, we lack the capacity to sustain our current consumption without reliance on the larger system. If we were cut off, for any reason, from the global food supply, it would be a difficult adjustment. In recent years, New England has made concerted efforts to support smaller local farms, often through tax incentives. Our farmers’ markets produce excellent food, but there’s still a long way to go toward self-sufficiency. It’s comforting, though, that our leaders are leveraging the capitalist system to safeguard us in the event that global food systems falter.

This tension between local resilience and global systems is a critical challenge. How do we create a system that can sustainably feed eight billion people healthy food within a global capitalist framework? I don’t claim to have the answer, but I believe the solution lies in a combination of large-scale industrial farms and smaller, local operations, alongside public and private partnerships that transcend borders. This will require collaboration from all stakeholders to meet needs, adjust flexibly, and maintain the health of supply chains. Individuals also have a role to play. Personally, though I struggle with it, I try to source as much of my food locally as possible, differentiate between wants and needs, and minimize waste. Leftovers are cherished in my household. But there is also a grace in this process, for myself and others—recognizing that change is never easy or linear, but forward it must go.

Returning to the artwork: if you’re familiar with my work, you might recognize some of the imagery here. I first conceived this image over a decade ago. Its original incarnation was a ballpoint pen sketch, and since then, I’ve created both an acrylic painting and a colored pencil version. Yet for some reason, I hadn’t revisited it in my stippling technique until now. People often ask why I include so many moons in my work. Honestly, I just think they’re cool. But I also see them as symbols of potential futures—signs of hope. Like many humans, I’ve always been fascinated by what lies beyond. I believe we look to the future with optimism, hoping that our descendants will have better lives. The solitary tree in this artwork, set against an adventurous sky with its multiple moons, reflects this narrative of hope. It suggests that our future path, while unknown, can only be found through a balanced awareness and a hopeful drive toward a better world. Perhaps focusing on food is a great place for all of us to start.

My personal journey into the world of local food began years ago when I started frequenting a nearby farm. At the time, I was living in Rhode Island and working at a bagel bakery just over the border in Seekonk, Massachusetts. We had a partnership with a local farm, Four Town Farm, right down the road. The asparagus from that farm was what first made me aware of the superiority of local produce. Fresh-picked asparagus is a world apart from what you can get year-round at a grocery store. The flavor is incomparable. Sadly, the window for this delicacy is brief, but it’s a beautiful prelude to the bounty that follows. Discovering such an incredible local resource was eye-opening, and it felt like something that should exist everywhere. The community it builds around healthy eating, combined with the reduced carbon footprint, strengthens local resilience—a reconnection our country could benefit from. I encourage my readers to seek out their local farms and see what they have to offer. You might be amazed.

This world is full of contradictions. When Richard Nixon spearheaded the first Farm Bill in the United States, the stated goal was to feed the world. I believe that, at its core, this was a genuine motivation. However, I’m not naive—there were certainly other, less noble interests at play. Large agribusinesses have succeeded in producing more food, but at a cost. They deliver cheap food, generating massive profits for a few, who likely don’t even eat the food they produce, much like Frankenstein’s monster. They dine on far more nutritious fare. This is just one more layer of inequity in our system. Yet it’s not the sole problem. Large-scale agriculture has lifted many people out of poverty and reduced hunger. But now is the time to go further. We need to recognize that something as elemental as food should nourish more than just our bodies. For many, it only sustains life on a basic level. Change will require a broad range of inputs at all levels of society. For the average person, it can begin with simple decisions about what we place on our tables—where it comes from, and how it enriches our lives beyond just filling our bellies.

I hope, as always, that you enjoy the artwork and the writing. If you would like to engage further please leave a comment. I promise I will get back to you.

Doug